Art Under Occupation and Beyond: Contesting Expressions of Identity and Memory in Contemporary Tibetan Art

Eesha V. Sheel

Eesha V. Sheel recently graduated from the School of Liberal Arts and Humanities at O.P. Jindal Global University, India where she pursued a self-designed major in History, Sociology, and Anthropology. She is interested in pursuing interdisciplinary research that brings together visual, material, and literary sources to study social institutions of gender, race, historical trauma and violence, and notions of home and belonging. She is going to be starting her master’s degree in September 2023.

Abstract

Contemporary Tibetan art has continued to play an important role in the global art movement as well as Tibetan politics as a means of expressing varying notions of Tibetanness and resisting the occupation of Tibet by the Chinese Communist Party. Fashioning a sense of Tibetanness has often been characterized by the subjective experiences of Tibetan artists. While some artists have migrated out of Tibet, others have remained settled in occupied Lhasa to practice their art. Some artists have never had the chance to visit Tibet, having grown up in exiled Tibetan communities in India and the West. These experiences have led to the rise of contesting ideas of Tibetanness that reflect the debates around Tibetan nationalism both within occupied Tibet and in the diaspora. This essay discusses the works of three contemporary Tibetan artists, Gonkar Gyatso, Nortse, and Tenzing Rigdol, focusing on how they express their own notions of Tibetanness through their art. While building upon existing scholarship on Tibetan art, I have also analyzed some of the newer works by Nortse that were produced during the COVID-19 pandemic to further discuss how global events continue to shape and affect Nortse’s art under occupation. Furthermore, I have also aimed to analyze contemporary Tibetan art alongside prevalent concepts within the domain of memory studies, namely discussing Pierre Nora’s “sites of memory” and Marianne Hirsch’s concept of “post-memory” to elucidate how art and visual culture can become crucial tools to preserve and carry down historical trauma and memory in the absence of a unified geographical identity.

Art Under Occupation and Beyond:

Contesting Expressions of Identity and Memory in Contemporary Tibetan Art

Art has been, and continues to be, an important medium of representation of identity, society, history, and politics. Not only does it allow the artist to construct a sense of self, but also to communicate the same to their audience(s), paving the way for dialogue and alternative perceptions of their work. As a political tool, art can help facilitate movements of resistance, particularly under heavily censored regimes or as an addition to the creative literature around social issues, ranging from feminism or environmentalism to geographical occupation, war, and forced migration. In the case of Tibet, art has become an important medium of exploration of Tibetan identity and the communication of the same to global audiences. Contemporary Tibetan artists have grappled with issues of occupation, censorship, and the erasure of cultural heritage while also attempting to understand their own Tibetan identity, leading to the production of contesting notions of Tibetanness that often reflect debates around Tibetan nationalism, exile, and alienation being discussed both by Tibetans living in Tibet and by the Tibetan diaspora across Asia and the West. The Tibetan experience of occupation has not only been characterized through violence, intergenerational trauma, and a loss of identity, but has also encouraged Tibetans to contend with the desecration and subsequent mystification of Tibetan culture and history. Keeping this context in mind, this essay aims to highlight the works of three contemporary Tibetan artists, Gonkar Gyatso, Nortse, and Tenzing Rigdol, and analyze the construction of varying notions of Tibetanness and Tibetan nationalism in their works, putting particular emphasis on elements of self-fashioning, trauma, memory, and resistance against the censorship and oppression of the Chinese Regime as well as their use of art in keeping the issue of Tibet alive in contemporary global politics.

Tibet was brought under the control of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1951. This was a result of the Seventeen Point Agreement that was signed between the PRC and the Tibetan government. However, confusion and concern for the Dalai Lama’s safety and growing sentiments of separatism continued to affect the region, increasing the tensions between the Tibetan and Chinese people. This context paved the way for the 1959 Tibetan Uprising, which saw protests erupt in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, and violent clashes between the civil population and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The uprising resulted in the Dalai Lama escaping from Lhasa in 1959 and saw many waves of migration of Tibetans to India and Nepal in the following years. Shortly after the Dalai Lama’s escape, Chinese security forces successfully re-captured Lhasa. Soon after, the Maoist Regime launched the Cultural Revolution as a socio-political campaign to eradicate elements of traditionalism and capitalism in the whole of the PRC. Regions that housed significant ethnic minorities, such as Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Tibet became a focus for the Chinese Red Guards to carry out their attack against the “four olds,” i.e. old ideas, old cultures, old customs, and old habits.

In Tibet, the Cultural Revolution was realized through an attack on the “vestiges of the old society and its ‘decadent’ customs” (Dreyer 101). This included heavy censorship being imposed on Buddhist imagery as well as strict regulation and prohibition of the practice of Buddhism (Misra 194). Thousands of Tibetan monasteries were either looted or reduced to rubble as part of the campaign, and according to some reports, Tibetan monks were forced to participate in the destruction of their own religious shrines and images (Dreyer 105; Harris 65). The Potala Palace, which is the residence of the Dalai Lama and perhaps one of the most identifiable symbols of Tibet, did survive the Cultural Revolution mostly intact. However, it went on to become a key building (alongside some re-constructed monasteries) for the “Chinese Communist Party’s claims to legitimacy on its ownership of China’s heritage and its efforts to push for an ethnocultural definition of national identity wherein minorities have been (in theory) ‘happily’ assimilated” (Harris 66). This was facilitated through the re-enforcing of an exoticized view of Tibet as “Shangri La” and the Tibetan people as “specimens of an unchanging traditionalism,” with the Potala Palace being emptied out, de-sacralizing it in the eyes of Tibetans (Harris 66). The removed relics and items were then placed in the neutralized space of the Tibetan Museum, which opened in 1999 to overtly communicate the Chinese government’s agenda “with panels explaining that the objects displayed were, like the territory of Tibet itself, inalienable possessions of China” (Harris 66-67). Therefore, the experience of occupation in Tibet has not only been limited to the experience of violence and intergenerational trauma, but also the active erasure, destruction, and the subsequent exoticization and mystification of their visual and material culture.

The Cultural Revolution is an important trigger for many contemporary Tibetan artists, particularly those who are based in Lhasa or started their practice in Tibet. This is most noticeable in the works of Gonkar Gyatso, a London-based Tibetan artist who started his art practice in Lhasa after receiving training in Beijing. Recounting his experience of growing up under the Maoist regime, Gyatso expressed his disorientation and alienation from Tibetan history and culture as someone who had “always looked at Tibet as a Chinese person would have done” (Gyatso 148). His view of Lhasa upon returning from his studies in Beijing in the early 1980s was also characterized by the liberalization of the region, wherein media and art from the rest of the world was now making its way into occupied Lhasa as a result of Beijing’s Open Door Policy, and because the Chinese had lifted some of the stringent prohibitive policies on the practice of Buddhism in the region (Misra 194-195). While there was still much propaganda around the representation of Tibet by China, the new developments in Lhasa, as well as Gyatso’s determination to “remove the Sinicization of Tibet” from his aesthetics, led to the production of some of his early works in Tibet. The most striking of these was the Red Buddha (1989) which featured an identifiable outline of the Buddha in black surrounded by red paint on a cotton canvas (Fig. 1), symbolizing the “violence and bloodshed faced by Tibetans under the Cultural Revolution” as well as calling for a “re-activation of the presence of the Buddha in this region” (Allison 39; Harris 702). The Red Buddha served as Gyatso’s attempt at engaging with his Tibetan identity under a highly authoritative regime by producing and exhibiting overtly political works in underground art guilds, such as the Sweet Tea House, that focused on the reclamation of Tibetan identity, closely linked to and rooted in the geographical region of occupied Tibet.

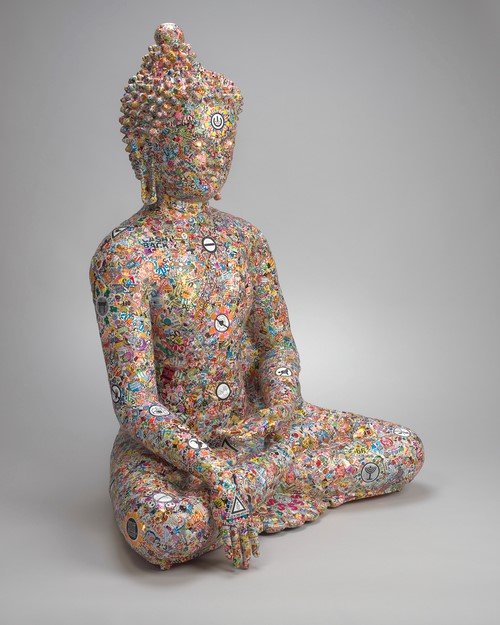

However, a shift in his works can be observed after his migration to India in the early 1990s, which provided refuge to not only the largest population of Tibetan diaspora but had also been housing the fourteenth Dalai Lama after his escape from Lhasa in 1959. Gyatso was curious to learn more about the traditional thangka paintings that were central to Tibetan art history but had been banned in occupied Tibet during the Cultural Revolution. However, Gyatso’s interaction with the Tibetan community in exile resulted in conflicting feelings. Gyatso acknowledged that learning traditional thangka painting in Dharamshala, which has continued to house the Dalai Lama and serves as the center for the Tibetan government-in-exile, allowed him to learn more about the history, art, and culture of Tibet than what was taught in Maoist China. But he also found himself at odds with the notions of Tibetanness being practiced and defined by the community in exile. Describing his Tibetanness as an inseparable part of his identity, while at the same time wanting to expand his expression of art and identity beyond tradition, led to his disappointment with the conservative and rigid socio-cultural and religious practices of the Tibetan refugee community in India and prompted his migration to the west (Gyatso 150). In London, Gyatso’s art evolved again to incorporate Western styles of representation, particularly the use of pop-art materials such as stickers alongside traditional Tibetan Buddhist symbolism. In Excuse Me While I Kiss The Sky (2014), Gyatso not only pays homage to the Jimmy Hendrix song “Purple Haze” and the politically charged decade of the 1960s, both for the West and for Tibet under the Cultural Revolution, he also creates a globalized image of the Buddha, covered in street signs and stickers, indicating the commodification of Buddhist symbols beyond Asia (Fig. 2).

While the Buddha remains an important symbol in his work, Gyatso’s expression of his sense of Tibetanness can be best observed in his photo series of self-portraits titled My Identity (2003). The four photographs depict the four contesting expressions of Tibetanness that Gyatso has had to negotiate through his life, travels, and art (Fig. 3). While the composition of the photos remains the same, with Gyatso seated in front of a canvas and facing the camera, the elements around him, including the scenes on canvas, his clothing as well as the items decorating the space around him, change in each photograph to represent the various ways in which his Tibetan identity has been fashioned and defined. The photographs can be read in biographical chronology, with the first showing Gyatso dressed as a thangka painter with a traditional painting of the Buddha on the canvas, followed by the image of him as a “Sinicized-Tibetan” painting a portrait of Mao Zedong. The third image shows him as a refugee artist in India, painting symbols associated with the historic and traditional images of Tibet such as the Potala Palace, and the final image shows him in his studio in London, as a contemporary Tibetan artist having negotiated and accepted his Tibetan identity and style of art (Allison 40; Harris 713). While the series as a whole represents Gyatso’s conflict over the definition of his Tibetanness, it also communicates his negotiation with themes of trauma and indoctrination under the Maoist Regime, his dissatisfaction with the Tibetan exile community in Dharamshala, India, and his efforts to deconstruct myths and stereotypes around the fashioning of Tibetan identity both within Tibet and in the Tibetan diaspora. For Gyatso, occupying a space in the Western contemporary art world has not only allowed him a sense of liberation and freedom of expression (Gyatso 150), but has also helped him understand his Tibetanness as a product of a constantly changing and highly fluid Tibetan culture that is marked by contestations between tradition and modernity.

Notions of Tibetanness have not developed in one direction, that is, with the migration of Tibetans outside of Tibet. While there are many artists who are part of the Tibetan diaspora across Asia, Europe, and America, some contemporary Tibetan artists have also chosen to remain in Tibet to practice their art. This has been the case for Lhasa-based artist Nortse (born Norbu Tsering), whose art has dealt with both global issues as well as those pertaining to Tibet while firmly basing his Tibetan identity in Lhasa. Like Gyatso, Nortse’s early work was a response to the experience of censorship, violence, and oppression under the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. His mixed-media piece Red Sun (2006) presented a broken Buddha statue placed in the center of a red sun, alluding to the erasure of Tibetan Buddhism during the Cultural Revolution (Fig. 4). The use of the color red and the symbol of the red sun not only symbolize the violence, bloodshed, and destruction of Tibetan life and heritage, but may also be a reference to the Chinese Communist Party, overtly calling out the regime’s brutal invasion, occupation, and oppression in the region.

Nortse’s art also evolved with time as his engagement with modern art styles and experimentation with different mediums allowed him to define his Tibetanness in distinct ways. His series of self-portraits represent the various facets of his Tibetan identity while also engaging with wider themes of environmentalism, alcoholism, and erosion of and alienation from one’s own culture. In Release From Suffering (2007), Nortse is seen with his hands tied up with white bandages in front of him, opening up to the sky with paper butterflies containing the Tibetan script emerging out of them (Fig. 5). The work invokes a shackled image of Tibetan identity, particularly the erosion of Tibetan language and script, which appears distinguishable yet barely legible in the artwork. Not only does the image serve to remind its Tibetan viewers of the importance of the preservation of the Tibetan mother tongue, but also defines language as an essential part of the construction, defining, and practicing of Tibetan identity. Nortse’s message about the importance of preserving and transmitting the Tibetan language also acts as a reminder for the Tibetan diasporic populations, particularly in North America and Europe, to continue to impart Tibetan cultural values and norms to their children, a task that is quite hard considering the challenges that have emerged out of cultural clashes and a dual desire to both retain Tibetan heritage while also being acculturated into mainstream Western culture and education (Giles and Dorjee 149-150). In White Tablecloth (2008), Nortse sits at a table wearing a yellow tank top and a red tie along with a Mickey Mouse face mask. He is surrounded by a baby bottle and a stack of books written in Mandarin (Fig. 6). The composition invokes the various issues that Nortse’s art focuses upon alongside the representation of his Tibetanness. The baby bottle may be alluding to underage drinking, and the books may be referring to the occupation and subsequent imposition of Mandarin against the erasure of Tibetan language, culture, and identity. Using a tie and a Mickey Mouse face mask may also be interpreted as symbols of globalization, showcasing the exposure to Western art, media, and culture in the Tibet Autonomous Region following China’s liberalization policies of the 1980s and 1990s.

Unlike Gyatso, whose exploration of Tibetan identity included the shedding and re-fashioning of various aspects of his sense of self through his travels, Nortse’s definition of Tibetanness includes the addition and assimilation of global symbols and issues while firmly rooting his identity in the geographical region of occupied Tibet. Nortse continues to reside in Lhasa, but most of his recent work has shifted away from explorations of individualistic notions of his Tibetanness to incorporate issues of environmentalism and alcoholism while connecting them to contemporary Tibetan politics. This evolution comes from his need to “change his style of expression every once in a while, including his technique and medium, because for him, ‘duplicating’ himself is a painful experience, making it difficult for him to continue using any one method for very long” (Nortse). Nortse, reflecting on his Tibetanness while living in occupied Tibet, has materialized the need for a more fluid and versatile form of expression of Tibetan identity, one that does not stick to rigid patterns of self-fashioning, but rather allows him and his art to grow with the socio-political changes of the time. It also allows him to break free from the unidimensional constructs of the “refugee/occupied artist” and expand his body of work to include subjects that complement Tibetan politics beyond the definition of identity. This is observable in Nortse’s latest series of works exhibited under the title The Golden Earth in 2023. The title piece, The Golden Earth (2021) is a collection of Tibetan prayer flags and various found objects such as a watch, sieve, and pistol put together into the shape of a cloud symbolizing the aftermath of the detonation of an atomic bomb (Chuk Hang). The use of Tibetan prayer flags alongside miscellaneous items in the composition of a popular symbol of war and conflict works towards situating Tibet within larger global narratives of violence, occupation, and conflict while also acting as a warning sign for contemporary socio-political crises faced by humanity, namely nuclear and ecological disasters as well as the global pandemic (Fig. 7). His other works in the series, also having been produced during the COVID-19 pandemic, deal with similar themes of uncertainty and confusion amid highly volatile and political climates.

While Gyatso’s exploration of Tibetanness is rooted in his migration from Tibet to India and to London and the creation of his hybrid identity, Nortse’s Tibetanness is rooted in the geographical land of occupied Tibet, one that is not untouched by forces of globalization. However, both artists use similar symbols of Tibetan identity to communicate their sense of self and interact with their Tibetan heritage. The most common and easily identifiable of these images are the Buddha for Gyatso and Tibetan prayer flags and the Tibetan script for Nortse. These symbols become what Pierre Nora terms Lieux de mémoire or “sites of memory” for their Tibetan audiences as they become “embodiments of a memorial consciousness that has barely survived in a historical age that calls out for memory because it has abandoned it” (Nora 12). These symbols act as triggers for Tibetan audiences, both in exile and those residing in the Tibet Autonomous Region, to remember their Tibetan identity and history while also carrying the memory of a pre-occupation Tibet into the future. Another important role that contemporary Tibetan art plays is that of invoking nostalgia among the older generations of Tibetan refugees as well as allowing younger Tibetan exiles to connect with their heritage. The latter can be facilitated through the exploration and understanding of Marianne Hirsch’s concept of “post-memory,” which refers to the memory of the descendants of those who have survived historically violent and oppressive events (Hirsch 8). Post-memory does not imply that one is beyond memory, but it is rather characterized through “generational difference and a deep personal connection” and “reflects back on the memories of the survivors, revealing them to be equally constructed and mediated by the processes of narration and imagination” (Hirsch 8-9). In the context of Tibet, post-memory functions in terms of carrying down the historical legacy, trauma, and violence of occupation as intangible narratives for the descendants of Tibetan exiles who have never visited their homeland but have constructed a sense of Tibetanness based on the cultural and social norms and oral histories about the heritage and occupation of Tibet.

The concept of post-memory can be further explored by looking at Tenzing Rigdol’s installation Our Land, Our People (2011), which consists of a constructed platform containing approximately twenty thousand tons of soil imported from Tibet (Fig. 8). The site-specific installation was constructed in Dharamshala, India, the seat of the Tibetan government-in-exile and home to the largest population of Tibetan refugees in India. The installation invited Tibetan refugees living in Dharamshala to stand upon and interact with the soil of their homeland and even encouraged them to take some of it with them (Fig. 9). Choosing Dharamshala as the site for this installation was important not only because of the large population of Tibetan exiles, but also because of India’s relationship with Tibet, both in a historical as well as political sense. Tibet has looked upon India as a major site for the development and spread of Buddhism throughout history and continues to maintain a symbiotic relationship with India given that it has provided refuge to not only the spiritual leader of Tibet, the Dalai Lama, but also to thousands of Tibetans. However, what is interesting to note is that India is not a signatory of the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 protocol and therefore does not have a well-defined policy on refugees despite having welcomed Tibetan exiles following the 1959 uprising. This has rendered a sense of liminality to the Tibetan diasporic experience in India, wherein the Tibetan refugees experience a state of in-betweenness characterized by a sense of statelessness and conflicting ideas about identity and belonging (Gupta 331). However, this sense of liminality has also led to new perceptions of exile and Tibetanness, with exile becoming a “moral project that privileges statelessness to offer a counter-narrative to Chinese claims over Tibet” (333). Exile then becomes a critique of the Chinese government’s brutal occupation of Tibet and is practiced as a choice, a facet of Tibetan identity that acts as a reminder of the fight to eventually return to a free Tibet (333).

Against this background, Rigdol’s installation encourages the Tibetan exile community in Dharamshala to not only remember their identity as Tibetans belonging to Tibet, but to further allow younger generations of Tibetan refugees to translate, even for a brief moment, their intangible post-memory narratives into a tangible, lived experience by touching and interacting with the soil of Tibet, a land they have never visited yet could now imagine as a real place and not just an abstract description characterized by stereotypical or fantastical depictions of Shangri-La or the “Roof of the World.” Rigdol’s installation is also rooted in his own sense of alienation from Tibet. Having grown up in the United States, Rigdol came to be a carrier of post-memory of Tibet, learning about it from his father and developing a disconnected and slightly fantastical view of his homeland. The installation, therefore, allowed him to also connect with his Tibetan history and heritage alongside other Tibetan refugees. The installation also served the purpose of bridging the gap between art and the public. While Gyatso and Nortse have produced powerful works of art throughout their career, the accessibility of contemporary art remains limited when it comes to reaching non-Western audiences as well as Tibetan exiles who do not have the means to visit the elite space of an art gallery to view these pieces. Rigdol’s installation, on the other hand, allowed the public to actively engage with art while also participating in the process of fashioning their own Tibetanness through a communal process of sharing their lived experiences of exile, keeping alive their fight to preserve Tibetan culture as well as holding on to the hope of seeing Tibet liberated in the future.

Contemporary Tibetan art has contributed significantly to the Tibetan cause by spreading awareness about Tibetan culture and history as well as keeping the issue of Tibet alive in contemporary global memory. Tibetan art has allowed artists to reflect and introspect about their own identity against the socio-political developments in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Contesting notions of Tibetanness have emerged in contemporary Tibetan art, ranging from Gonkar Gyatso’s evolution of a hybrid identity that is rooted in Tibetanness while also embracing Western art, aesthetics, and culture to Nortse’s experimentation with mixed media art under occupation that emphasizes the fluidity of notions of Tibetanness, situating Tibet within larger global processes and movements. Tibetanness as an experience characterized by alienation and dissociation is central to Tenzing Rigdol’s work, particularly in representing experiences of liminality and exile of the Tibetan diaspora. The Tibetan experience of occupation also remains unique given the differing debates on the meaning of Tibetan nationalism and how it is practiced in occupied Tibet compared to the politics of the exile community, with important questions emerging about the very concept of Tibetan liberation and how it might or might not be realized in the future. While this essay has briefly discussed how contemporary Tibetan art can be crucial to understanding the preservation and transmission of historical trauma and memory, exploration into the role of Tibetan aesthetics in the domain of memory studies, particularly the role of sites of memory and post-memory in the construction of Tibetan nationalism both within and outside of Tibet, remains relatively undiscussed and therefore calls for further research on how art and memory can help define notions of Tibetanness under occupation and beyond.

Works Cited

Allison, Martha. “On The Beginning of Contemporary Tibetan Art: The Exhibitions, Dealers, and Artists.” Virginia Commonwealth University, Jan. 2009.

Chuk Hang, Wong. “The Golden Earth.” Rossi-Rossi, 2023, www.rossirossi.com/exbhition/the-golden-earth. Accessed 21 May 2023.

Dreyer, June. “China’s Minority Nationalities in the Cultural Revolution.” The China Quarterly, no. 35, 1968, pp. 96–109. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/652436. Accessed 6 July 2023.

Giles, Howard, and Tenzin Dorjee. “Cultural Identity in Tibetan Diasporas.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, vol. 26, no. 2, Taylor and Francis, Mar. 2005, pp. 138–57.

Gupta, Sonika. “Enduring Liminality: Voting Rights and Tibetan Exiles in India.” Asian Ethnicity, vol. 20, no. 3, Routledge, Feb. 2019, pp. 330–47.

Gyatso, Gonkar. “No Man’s Land: Real and Imaginary Tibet: The Experience of an Exiled Tibetan Artist.” The Tibet Journal, vol. 28, no. 1/2, 2003, pp. 147–60. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43305422.

Harris, Clare Elizabeth. “The Buddha Goes Global: Some Thoughts Towards a Transnational Art History.” Art History, vol. 29, no. 4, Wiley-Blackwell, Sept. 2006, pp. 698–720.

Harris, Clare. “The Potala Palace: Remembering to Forget in Contemporary Tibet.” South Asian Studies, vol. 29, no. 1, Taylor and Francis, Mar. 2013, pp. 61–75.

Hirsch, Marianne. “Family Pictures: Maus, Mourning, and Post-Memory.” Discourse: Journal for Theoretical Studies in Media and Culture, vol. 15, no. 2, Wayne State UP, Jan. 1993, p. 1. digitalcommons.wayne.edu/discourse/vol15/iss2/1.

Misra, Amalendu. “A Nation in Exile: Tibetan Diaspora and the Dynamics of Long Distance Nationalism 1.” Asian Ethnicity, vol. 4, no. 2, Routledge, June 2003, pp. 189–206.

Nora, Pierre. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux De Mémoire.” Representations, vol. 26, University of California Press, Apr. 1989, pp. 7–24.

Nortse. “Nortse Self Portraits - the State of Imbalance- Rossi-Rossi.” Asian Art, 2008, www.asianart.com/pwcontemporary/gallery2/5.html. Accessed 21 May 2023.